Playing with Power – BDSM in Games

How are BDSM and power dynamics represented in games, and what can that teach us about love, life and games?

In this blog post I’m exploring what BDSM and games have in common, and how BDSM and power dynamics are represented in indie games. It’s based on the talk “Explicit Power Dynamics – BDSM in Games”, that I’ve given at Lyst Summit 2017, and at QGCon and IndieCade 2018. A video recording of the talk from QGCon can be found here.

BDSM is about playing with power dynamics

BDSM is an umbrella term for a number of sexual or erotic practices. The abbreviation stands for Bondage/Discipline, Dominance/Submission, and Sadism/Masochism. It’s often also grouped together with fetish culture, from the outside often characterized by fetishized materials and clothing, such as latex and PVC, uniforms, and bondage-like harnesses, but what which can be so much more than that.

Within the subgroups of BDSM there are an almost infinite number of expressions that BDSM can take, all having something to do with playing with power dynamics. There is shibari, japanese bondage, edge play, involving for example blood and other body fluids, there is role-playing, for example age play and pet play. For the uninitiated, some of these practices can seem a bit scary, but for those practising them, they are considered positive and are often empowering for the individual.

BDSM is still outside of the norm. For a long time it was considered a mental illness, but the last couple of years this view has changed a bit. BDSM has become part of popular culture, for example through the book series 50 Shades of Grey by EL James and the feature films based on the series.

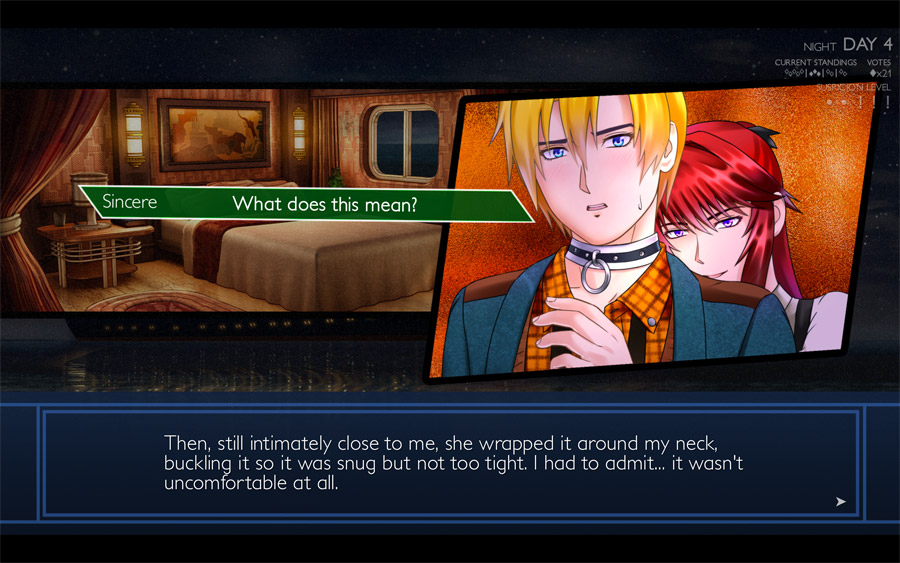

Flavors of BDSM is kind of a common ingredient in manga and anime, especially in boys’ love, and in anime ships – fan works in which fans pair up characters from anime, manga and games. And lately we have seen fetish expressions take a place within fashion. In fashion-based subcultures such as pastel goth, no-one raises an eyebrow if someone wears a harness or a choker, especially not if it’s pink. BDSM has also become part of some games, for example Ladykiller in a Bind (2016) by Christine Love, where it’s an integral part of the narrative. This is also a game I’m heavily inspired by in my own game creation.

Ladykiller in a Bind by Christine Love

Why is BDSM interesting from a games perspective?

BDSM actually has quite a lot in common with games. When I’m asked to speak about what games are, I often state that games require clear boundaries, clear rules, and clear feedback, among other things. These requirements are also part of the play of BDSM. Because make no mistake: BDSM is play, albeit sexual play – and play has as you might imagine a lot in common with games.

In Homo Ludens (1938) the philosopher Johan Huizinga defines play as:

… a voluntary activity or occupation executed within certain fixed limits of time and place, according to rules freely accepted but absolutely binding, having its aim in itself and accompanied by a feeling of tension, joy, and the consciousness that it is ‘different’ from ‘ordinary life’.”

That definition rather does apply to games – but it also applies to BDSM. In BDSM the rules are essential. Consent and communication is crucial. The power dynamics are visible, and clearly laid out for everyone involved. The players of BDSM often have specific roles, and within a play session a number of (often beforehand negotiated) actions can take place. All players join voluntarily and have the power to cancel actions they are not comfortable with, and break the play at any time – sometimes through the use of safe words, and sometimes through participants checking in a lot with each other. But this is of course a matter of communication, and as everyone knows, the art of communication can be a tricky one.

Can power dynamics in relationships be explored through games?

Games are interactive and as an interactive medium, a game’s primary expression lies within its mechanisms, and how those are designed to evoke reactions and feelings within the player. Avery Alder, a game designer from Canada, who designs storygames and table-top role playing games, held the, for me, eye-opening talk ”Imagining Ourselves: Queer Mechanics and Queer Games” at Proud & Nerdy, Malmö Pride, a couple of years ago. A video recording of this talk can be found here.

Alder said that:

Games aren’t slideshows. Games are systems. Systems aren’t objective or neutral. Games present us with the designers’ biases. All mechanics reinforce worldviews & politics. We’ve been playing straight games!”

What I think Alder means is that it is important that we, as game creators, take responsibility for what we present in our games, both topic- and character-wise, but even more so, in the mechanics of the games. Because the game mechanics are the real heart of the game – it’s essence, so to speak. One way of taking responsibility for the games’ essence is through introducing norm-challenging game mechanics. Alder presented in the talk six possibilities for queering games, with concepts such as The fruitful Void and Character Non-monogamy.

Explicit Power Dynamics

Another of the mechanisms that Avery introduced is Explicit Power Dynamics. Explicit power dynamics is about making power structures visible, and to let the players explore or even change them. Power dynamics are often taboo – since talking about power might make people request change … and that makes them even more taboo to play around with. Through making power dynamics visible, we can become aware of how they function, we can process them and learn about how they play out in our relationships – and thus we can also start to challenge them – if we want to.

In Robert Yang’s game about consent, boundaries and BDSM, Hurt me plenty (2014) you get to spank a guy who is standing on all four on the floor. He does like spanking, but he, as every human being, has his boundaries – and you better respect them. But as a player, you have the power to do whatever you like. You can spank him harder than he enjoys, but it won’t go unnoticed. If you surpass the receiver’s boundaries, the game will end and you might even be banned from playing for a while.

Hurt me Plenty by Robert Yang

When playing, I did this, and the feeling of violating another person’s borders was uncomfortable, a physical feeling of cringe, and I felt disgust towards my own actions. Without saying aloud what I would take away from this game, it got to me, simply through my own actions and how they made me feel.

Somewhat similar but very different is the Consensual Torture Simulator by Merritt Kopas (2008). It’s a completely text based game which let’s the player explore how to take on the wish from their girlfriend to be spanked until she falls into tears. It’s a soft-paced game that let’s the player think about how to set up a session and also how and when to end it. Just as in Hurt me plenty, the player is in control over the situation and has quite a lot of power towards the receiver.

Consensual Torture Simulator by Merritt Kopas

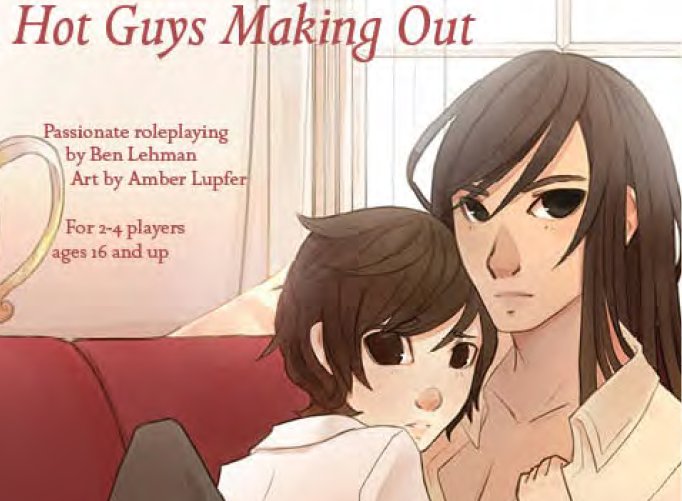

Another game that uses the mechanism Explicit Power Dynamics is the tabletop role-playing game Hot Guys Making Out (2013), by Ben Lehman, which Alder also uses as an example in her talk. This game centers around the forbidden passion between two main characters, Gonsalvo and Honoré, who have very different traits. Gonsalvo is very shy and timid, and has a hard time getting his emotions through. Honoré is the opposite. He is decisive, always taking action, and succeeding with what he takes on. In the game, you play one of the characters, and you use regular playing cards to perform actions. Every time Gonsalvo gets to play a card, he gets to tell about his emotions, and express his inner monologue, but he cannot take any actions (except for the special case when a heart is played). For Honoré, the opposite takes place. He only gets to perform actions, and can never explain or talk about his feelings, except as well, when a heart is played.

Hot Guys Making Out by Ben Lehman

This game is not about BDSM per se, but I think it might be the most clear example on how you could work with power dynamics as a game mechanic, letting power differences between the characters be conveyed through mechanisms. Since the power dynamics are so uneven in the setting, it’s also very easy to introduce BDSM play into the game, if you’d like that.

The games that want to be disobeyed

Since games have rules and give players instructions, and players most often voluntarily comply, one might argue that games are inherently dominant and players submissive. In her 2016 Kill Screen article The videogames that want to be disobeyed, Elise Favis exemplifies games that give contradicting instructions, or where players need to decide for themselves which “orders” from the game to obey and not.

One example of that is Tale of Tales The Path (2009), in which at the beginning the player is supposed to go Grandmother’s house and explicitly told not to stray from the path. If you do as the game tells you, the game will end in minutes. It’s first when you do stray from the path, you get to experience more of the game’s narrative.

Another example that Favis brings up is the indie platformer Loved (2010) by Alexander Ocias, in which the game’s narrator gives players rather arbitrary orders, which they can disobey if they want to. The narrator responds to player choices by praising them or harshly dismissing them.

Loved by Alexander Ocias

Favis writes that:

Loved’s confrontational mechanics of obedience and disobedience resemble dominant/submissive BDSM power dynamics and sexual practices. It places you in the shoes of a submissive by putting you under the spell of the narrator’s dominance. Even if you disobey, there’s an impression that you are nonetheless being led by the narrator’s leash.”

The games that challenge obedience gives another mechanical approach to working with power in games. By being self-aware of their mechanisms, they force the player to become aware of those too – and as Favis concludes, thus invites the player to set aside their comfortable routines.

The game and the player

The relationship between the player and the game is by extension also a relationship between the player and the game’s creator. As the one in charge of what the game will demand of players, I as a creator will be part of a negotiation. Putting (negotiated) power exchange and sometimes even violence upfront sometimes poses questions about fiction versus reality, and the players’ own limits.

One of the large advantages with fiction is that we can experience things in ways we otherwise wouldn’t, and therefore the boundaries within fiction can (and should) be a bit freer than in everyday life. In the end, that is one of the main points of play: getting the possibility to perform actions you wouldn’t normally do … to get to explore who you are, when you take a step out of the box. But that of course comes with the risk of players getting uncomfortable. And that is why we most often use content warnings and give players the opportunity to opt out. But even when given a choice to do or don’t, players might transgress their own boundaries, since deciphering and understanding one’s own limits can be very hard.

That said, I don’t think that feeling uncomfortable is necessarily bad when playing games. It might even be the goal, as in Hurt me plenty – you are supposed to feel uncomfortable violating the other person’s boundaries. The power is put in your hands, and you should use your agency wisely.

So, what can all this teach us about love and life?

Something that both playing games and practising BDSM can do for us human beings is offering the opportunity to try out new roles, new ways of acting, as well as making experiences that we wouldn’t get in everyday life. All of this can lead to expansion of the self, opening up for new possibilities. The experiences made in a safe setting, such as in play, can be transferred into everyday life, empowering the person.

To be able to expand and develop as a person, the playing-ground needs to be safe, and the communication with others needs to be clear, as well as based upon respect and trust. It requires a lot of guts to be clear towards others, revealing your secret wishes, fears and desires. This is something most of us try to achieve, failing and succeeding, over and over, in different situations and relationships, throughout life.

One way of practising communication and role-taking can be through playing games. Another way could be through practising and experiencing BDSM. A third – and in my opinion perfect – option is through playing (and making) games about BDSM.

Leave a Reply