Variations on Amnesia

Adaptations are very common in the domains of manga and anime, the most typical being that an original work of manga is adapted into anime. But there is a third media form that sometimes get adaptations too, namely games, and more specifically, the adventure game genre visual novel.

[This text was originally written as a final essay in the course Japanese Popular Culture Represented in Anime and Manga at Dalarna University. It contains major spoilers for the Amnesia game and its anime adaptation, so don’t read it if you want to avoid those.]

In this essay I will look into how the experience of a fictional work can be affected by the presence or abscence of interactivity. In an interactive work, the player gets to choose what path to take through a fictive work, something that can not be achieved in the same way in a linear story. When adapting such a story, some dramaturgical choices have to be made. Those might in turn affect the experience of the story, and this is what I will look into, by studying the visual novel Amnesia (2011) and its anime adaption Amnesia (2013).

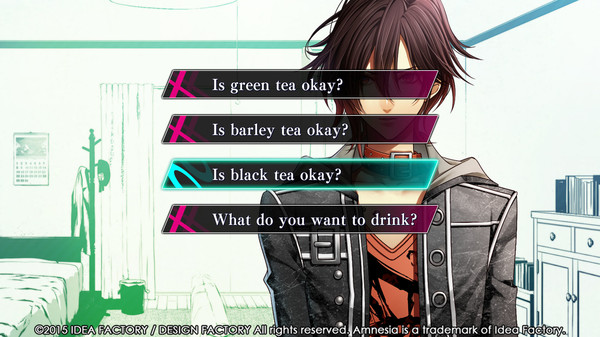

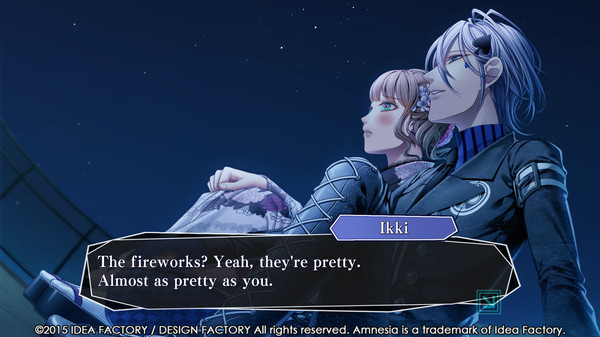

The Amnesia game was originally developed by Idea Factory & Otomate and released for PlayStation Portable in 2011. In 2015, the game was released in English as Amnesia: Memories. The visual novel’s action is driven mainly by text and dialogue, illustrated by character images, animations and backgrounds. The story is also affected by player choices, which changes what scenes the player gets to experience, and the endings of the game routes. Amnesia contains dating sim elements, which means that the player can choose between different love interests and explore those in game form. Since the main character is female and the love interests are male, the game is categorised as an otome (maiden) game, see for example The Visual Novel Database. The game’s popularity led it to be adapted into anime by the studio Brain’s base in 2013. On My Anime List, the anime is categorised as josei (targeted towards a female, young adult audience), mystery and harem.

Main Focus

My main focus in the essay is to look at:

- Which storylines from the game did the anime creators include in the adaptation, and which did they disregard?

- How does the player agency affect the experience of the story, compared to the linear version in the anime?

Since the original creation is the game, I chose to play the game before watching the anime, using the game as the base, and then compare the anime adaptation to it.

Analysis

Playing Amnesia

In Amnesia, you play a young woman who, due to colliding with the spirit Orion, has lost all of her memories. The player doesn’t have a visible avatar. Instead, Orion does most of the talking. He functions both as a sidekick to the heroine and as an instructor to the player.

The game takes place in four parallel worlds, and in each, the heroine wakes up to being in a relationship with a different guy: Toma, Kent, Ikki or Shin.

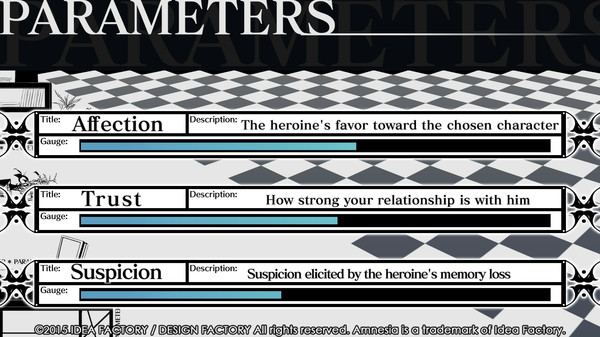

The story plays out during one month, in which the heroine has to regain her memories. If she succeeds, the ending with that particular character will be the best possible. There are different mysteries surrounding the characters, and the objective is to find out what relationships the heroine had with them before her memory loss. But it’s not certain that she can trust the character she’s with.

- In the Heart World, the heroine dates Shin, and she needs to find out who pushed her off a cliff. Could it be her boyfriend, or was it someone else?

- In the Spades World she dates Ikki, who’s so popular among the girls that he has his own fan club. The heroine needs to handle Ikki’s popularity and possible cheating, and discover what her true feelings are.

- In the Clover world, the heroine dates Kent, whom she always gets into fights with. The heroine needs to find out why she started dating him, since her friends and even Kent himself, claim that she didn’t particularly like him.

- In the Diamond World, the heroine’s childhood friend Toma claims to be her boyfriend. He is overprotecting, and soon the heroine starts questioning if he really wants to protect her, or if he’s rather trying to control her.

- And then there’s the Joker character Ukyo, who’s a recurring presence in all of the worlds. He’s a shapeshifter: sometimes he kills the heroine in a bad ending, and sometimes he’s the one who saves her.

After playing all of the four main routes, an extra route with Ukyo is unlocked, in which the player will get the explanation to how everything is connected.

Story Structure: The Time Cave

In the beginning of the game, the player chooses a route connected to a character. Depending on the choices made, the player will eventually get one out of at least four endings. They are categorised by the game’s creators as good, normal, or bad. Good means that the relationship ends in romance, and that the heroine’s memories are restored.

The game engine is designed to make it easy to replay the game, to get a new ending. But to do so, the player has to restart from the beginning. To play all the routes, the player is also required to restart. This means that the player is expected to play through the game a large number of times, something the game supports by letting the player fast-forward through text. The fast-forwarding pauses when there is a choice to make, letting the player change the outcome by choosing new alternatives. The players are presented with a list of all the possible endings, to see how many they have experienced and what is yet to explore. Using a walkthrough, a player’s guide, to make sure you reach all the endings is a common way to play.

In the blog post ”Standard Patterns in Choice-Based Games” (Ashwell, 2015), this kind of story structure is called a Time Cave and is especially suited for games that are meant to be replayed. In Amnesia, as in many other visual novels, players move in and out of the game to do so, restarting from the beginning and making save files before significant choices, to be able to replay if they get a bad ending. Breaking the fourth wall is a term to describe when a medium, for example a film, addresses the viewer through the camera (Wikipedia, 2020), letting them know that the medium itself is aware that the fictional world is a construction. Defining what might constitute a fourth wall break in a video game is hard (Conway, 2009), since players are active in other ways than for example film or theatre audiences. But when the player is asked to step out of the gameplay and search through the structure of the game for different story outcomes, it breaks the immersion in a way that I think resembles breaking the fourth wall. Visual novels designed in this manner invite the players to examine the game’s design, revealing some of its secrets to the player. On the other hand, it also opens up possibilities to be very upfront about the content and its variations, which in this case turns out to be significant for the experience of the story. As Conway proposes (2009), this might not be an actual fourth wall break, but rather an expansion of the magic circle of play (Huizinga, 1938/Salen & Zimmermann, 2003) to encompass the replaying, and integrate the variations into the story.

Watching Amnesia

So, what happens when this very complex story is transferred into twelve 25-minute anime episodes? One big difference between the two is a premise shift. In the game, the heroine has no knowledge of the different worlds, once she enters them. In the anime, the heroine is aware that she’s jumping between worlds. The main question shifts from ”is he my boyfriend, and can I trust him?” to ”why am I in different worlds, and is there a right one?” Instead of parallel worlds, separate from each other, the worlds are presented as a sequence of loops, repeated one after the other.

Regaining memories

The player’s most important objective is to regain the heroine’s lost memories. Entering each world, it’s obvious that the heroine is in relationships with the other characters, she just can’t remember them. Gradually, she gains more or less of her memories back. In the anime, her boyfriends instead quickly recaps much of the storylines to her. The lost memories aren’t the issue, as much as why there are different worlds, and why they are recurring. Throughout the anime, the heroine accepts what the characters are telling her without questioning them, while in the game, the main goal is to question the characters, and even the heroine’s own motives.

Since the relationships portrayed in the game range from being cute love stories to containing downright gaslighting and abuse, the answer to whether the heroine can trust her boyfriend or not varies a lot. The tension revolves around not knowing who you can trust, which can sometimes make it hard to build up favourable emotions toward the characters. That’s part of the game’s premise. But since the game’s exploration of the characters’ trustworthiness can’t be directly transferred into the anime, the creators have chosen not to include it at all.

Is the good ending the right ending?

Content-wise, the creators have chosen to mainly include content from the good endings, and disregard the alternatives. This is reasonable, since the storylines leading up to good endings contain the most information about the heroine’s lost memories. But by doing so, you could argue that the good endings are also chosen as the right endings, since there are no longer any alternatives. And this turns out to be somewhat problematic, especially in one of the storylines, the one with Toma.

Toma is a character who’s very overprotective toward the heroine. As the story progresses, the heroine is threatened by members of Ikki’s fan club, and in the pretense of protecting her, Toma goes very far. He lies to her about being her boyfriend, drugs her to keep her in check and finally puts her in a cage.

This game route can end in four ways:

- In the good ending, the heroine forgives Toma and accepts his actions as being made out of consideration.

- In the normal ending, she manages to run away. She’s still in love with Toma, but she never sees him again.

- In one bad ending, Toma captures the heroine after she’s fled, and puts her back in the cage, never to let her go again.

- And in the other bad ending, the heroine is killed by Ukyo, as she tries to escape from Toma.

But in the anime, there is room for just one storyline per character, and as the content is taken from the good endings, the heroine is given only one option: To forgive Toma.

In Stuart Hall’s Encoding/Decoding (2009), originally writen in 1973, he proposes three ways an audience member can decode a given message: They can choose to accept it as it’s intended by the sender and do a preferred reading, they can do an oppositional reading, where they rebel against the content, or they can negotiate with the message, trying to find an acceptable middle ground between the creator’s intentions and their own values, resulting in a negotiated reading.

In my thinking, the game, with its different outcomes, invites the player to make a negotiated reading. Since there are many variations, the player can decide which one to believe in. Even though one ending is proposed as the good one, the player doesn’t have to accept it. There are more alternatives to choose from. But in the anime, if you won’t accept the outcome where the herione forgives Toma for deceiving, drugging and kidnapping her, there is only the oppositional reading left.

The full story

After playing the four main game routes, a fifth route is unlocked, in which the player gets to date the half human/half spirit Ukyo. He has merged with a kami (a god of sorts) who’s trying to grant his wish to save the heroine from dying in one of the worlds. Fueled by the kami’s powers, Ukyo is traveling between worlds, trying to see his loved once again. But as he is an intruder, not meant to be in those worlds, he and the heroine can not co-exist there. Therefore, Ukyo is repeatedly either killed himself or forced to kill the one he loves, until he loses his mind altogether. He ends up as the shapeshifter, switching randomly between saviour and slayer.

Ukyo will eventually explain to the heroine (and the player) how everything is connected, including the reason for the amnesia. As his wish to save her life is finally granted, he no longer needs to travel between worlds, and the player gets to return the heroine to a normal life, either in a world where she’s together with Ukyo, or in one without him.

In the anime, where the worlds are recurring instead of parallel, the explanation for the events is somewhat modified. The recurrence is explained as being a result of the power of the kami merged with Ukyo. Each time the heroine dies, her mind is pushed into a new dimension, until she enters the last world, where Ukyo succeeds in not killing her, and thus ends the looping.

In the game, even though the world with Ukyo is presented last and contains the explanation and resolution, all the worlds still exist parallel to each other, and are so to speak of equal weight. They are all ”true”, and players can decide which one they like the most. Ukyo’s presence in all of the worlds, as well as his reason for killing the heroine, gets a reasonable explanation, but it doesn’t reduce the significance of the other worlds.

In the anime, Ukyo also explains to the heroine that he has been her slayer in the looping worlds, but as viewers, we have never experienced those events ourselves, as we did in the game. Every loop in the anime has been preceeded by the heroine’s death, but the connection to Ukyo is not explicitly shown. Since we are following a storyline without variations, the explanation for Ukyo’s presence and actions becomes more of a theoretical construction than in the game, where we have experienced those alternative events – being killed by Ukyo – firsthand.

Discussion

Knowing the full story from the game, and having already made my own interpretations obviously affected my experience of the anime. After finishing both works, I read reviews on My Anime List, to see how viewers who hadn’t played the game might perceive it. The reviews were very polarised: Many graded the series as a two or three out of ten, stating that they didn’t understand much of the story and the characters, while others graded it as a nine or ten, just because of the complex, layered story. Some of the comments were related to dramaturgical choices made by the creators, based upon the design of the game. For example, a recurring opinion was that the heroine was annoyingly passive and bland, and viewers were provoked by the fact that she didn’t even have a name (which is based upon the functionality of the game, where the players name the heroine themselves). Judging the anime from the same position as those who hadn’t played the game is impossible for me. I can only compare the differences between the two, based on the experiences I’ve made while playing. To get a more objective perspective of how the story would be perceived by viewers who hasn’t played the game, one way could be to do a more thorough analysis of the opinions expressed in the reviews.

Conclusion

The story structure of the game gives players the opportunity to explore the game world, based on their own preferences, with full knowledge that each variation is just one out of many. In the anime, some of the interpretations of the narrative were made by the creators, and were no longer up to the viewer to interpret freely. The complexity, with at least four different endings for each character route, as well as a playtime of around thirty hours to complete the game with all its endings, makes this kind of visual novel a tough challenge to adapt, especially into a anime series with just twelve episodes. The decision to focus on the content from the good endings and discard the alternatives might have been the only viable option, given the circumstances. But by doing so, some of the nuance of the game’s story was lost.

Deliberationg on the conclusion, I came to think of the concept: The medium is the message (McLuhan, 1964). Although not perfectly applicable, I do think that in this case, it’s very hard to extract the story from the game’s design and put it into a linear format. Game designers have previously stated (Alder, 2014, and Curran, 2015) that stories in games can not easily be stripped from the games’ mechanisms, their functionality, since they are connected in essential ways. In his 2015 talk at The Nordic Game Conference, Love & Violence, Ste Curran describes this with an almost poetical sentence: ”The mechanical story is the heart of the game.”

For this work, my conclusion aligns with theirs: The very essence of Amnesia’s message lies within its variability. It’s the knowledge about the variations, supported by the narrative structure and its content, as well as the game’s mechanisms, that gives the player the full experience of the story. Therefore, I believe that this story can’t be extracted from the game’s functionality without losing some of its depth.

Bibliography and references

Alder, Avery. Youtube, 2014. ”Imagining Ourselves: Queer Mechanics and Queer Games”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TMNndhgp_V4 . Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

Amnesia. Created by Brain’s Base. AT-X, BS11 Digital, KBS Kyoto, SUN TV, Tokyo MX TV, TV Aichi, TV Kanagawa, 2013.

Amnesia. My Anime List, 2020. https://myanimelist.net/anime/15085/Amnesia . Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

Amnesia. Visual Novel Database, VNDB, 2020. https://vndb.org/v7803 . Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

Amnesia: Memories. Steam, 2020. https://store.steampowered.com/app/359390/Amnesia_Memories/ Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

Ashwell, Sam Kabo. These Heterogenous Tasks, 2015. ”Standard Patterns in Choice-Based Games.” https://heterogenoustasks.wordpress.com/2015/01/26/standard-patterns-in-choice-based-games/ . Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

Conway, Steven. Gamasutra, 2009. ”A Circular Wall? Reformulating the Fourth Wall for Video Games” https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/132475/a_circular_wall_reformulating_the_.php . Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

Curran, Ste. Love & Violence: How we tell stories of love and violence, where we fail, and why. Nordic Game Conference, 2015.

Fourth Wall. Wikipedia, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fourth_wall . Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

Hall, Stuart. Encoding/Decoding. In Media and Cultural Studies, edited by Meenakshi Gigi Durham, Douglas M. Kellner. John Wiley & Sons, 2009.

Huizinga, Johann. Den lekande människan (Homo Ludens). Natur och Kultur, 1938.

Idea Factory & Otomate. Amnesia:Memories. PC version, 2015.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. McGraw Hill, 1964.

Salen, Katie, and Eric Zimmerman. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. The MIT Press, 2003.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

Pingback: Relationships and gameplay – Transcenders Media