Systems for Emotions – Knife Sisters

4 Comments

Comments are closed.

In this blog post, I’ll go into Knife Sisters as an example on how a game’s system is created to convey a story, and how the characters are chosen to play a part in that story. (Be aware, there will be spoilers!)

When we started working on Knife Sisters, I mainly only knew that the game would be about Leo, a 19-year old non-binary and pansexual person, sharing a flat with a few other people in a semi-large city. Leo was inspired by a real person who I spotted at the Pride Parade in Malmö. At a Pride Parade, many people are celebrating, but this person was standing alone, with broken angel wings, as the rain started to pour – and I got intrigued. Who were they? I couldn’t know, so I started making up stories in my mind. Eventually the fictionalized version of this person became the main character in Knife Sisters.

In the beginning of the game, Leo is portrayed to be indifferent and probably also a bit depressed. Then, the artist Dagger moves into the same apartment as them, and she claims to be part of the secret society Knife Sisters. She starts asking things of Leo, things that are sometimes really hard to obtain, such as getting blood from an innocent person. As the story progresses, the demands on Leo get higher and higher. But can Leo really do whatever Dagger asks of them, regardless of the cost?

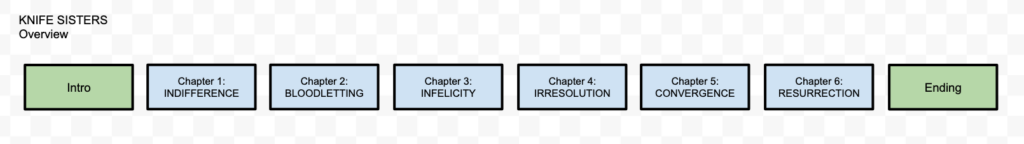

The game is structured into six chapters, each of them spanning one week. The game starts with one of the last scenes, where Leo wakes up in their room, remembering nothing from the night before, just knowing something bad must have happened. The player then has to go back six weeks in time to find out what actually transpired.

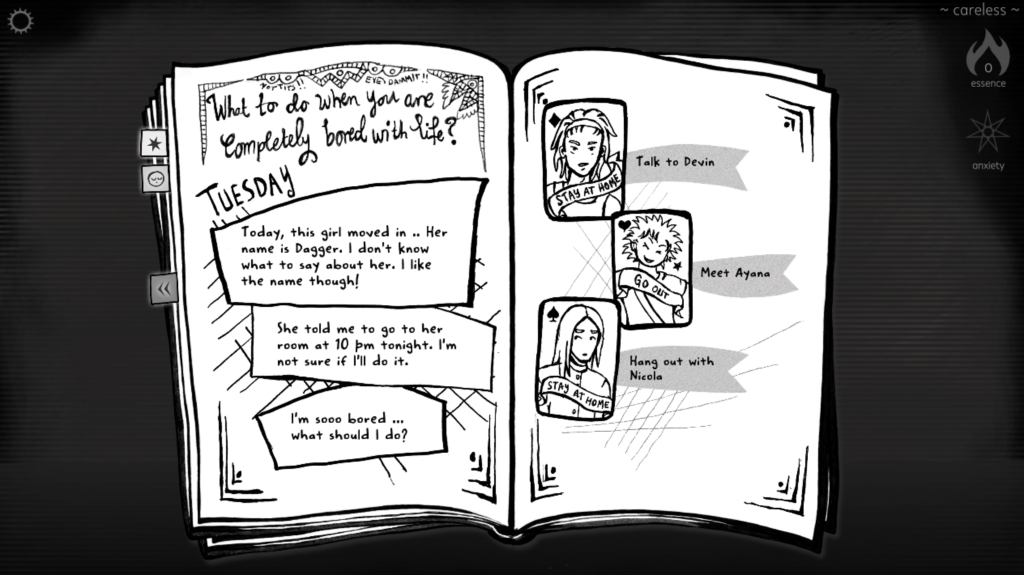

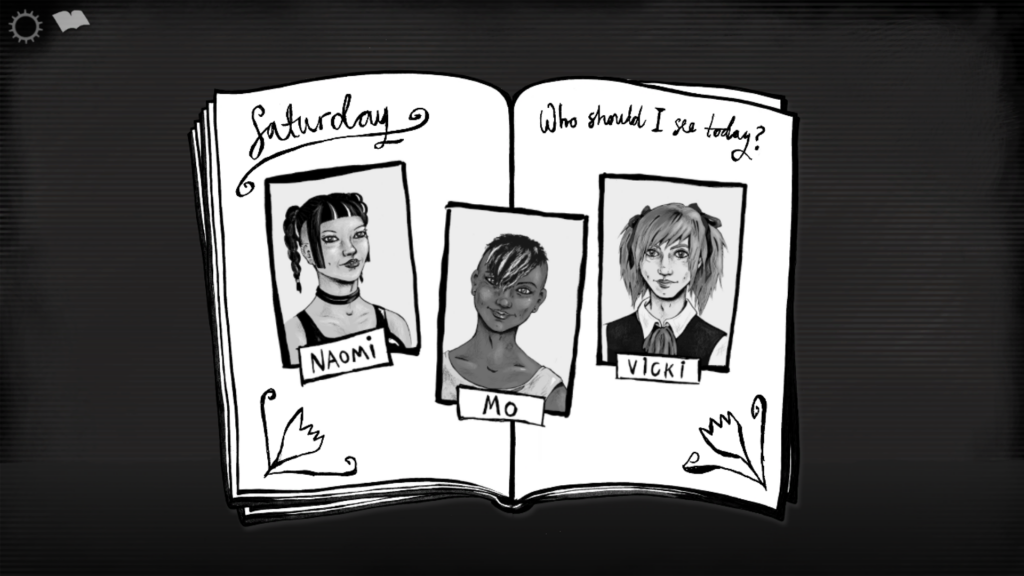

Each week/chapter in the game is also structured somewhat similarly, where on weekdays, the player uses Leo’s Diary to decide which people to hang out with, most often their friends and – later – lovers.

In the specific scenes, the player can make choices (mainly dialogue choices) that affect the outcome of the scene, which will also affect the ending, since some choices affect stats in the game. Each week, the player will play a couple of everyday scenes where they meet with different characters and try to meet Dagger’s demands.

At the end of the week, there is usually a bigger event happening, such as a party or a gathering of some kind, to have many characters in the game meeting at the same place, for instance a rave party or an occult fair.

As you can gather from this, the set-up of the game is rather fixed. There is a limited set of locations and characters, and of choices you can make in regards to the characters. The temporality of the game is also somewhat fixed: Since you start with playing one of the last scenes in the story, we know this outcome will be there no matter what else changes in the story. But although there are set premises, within those, the player has the freedom to decide what will happen.

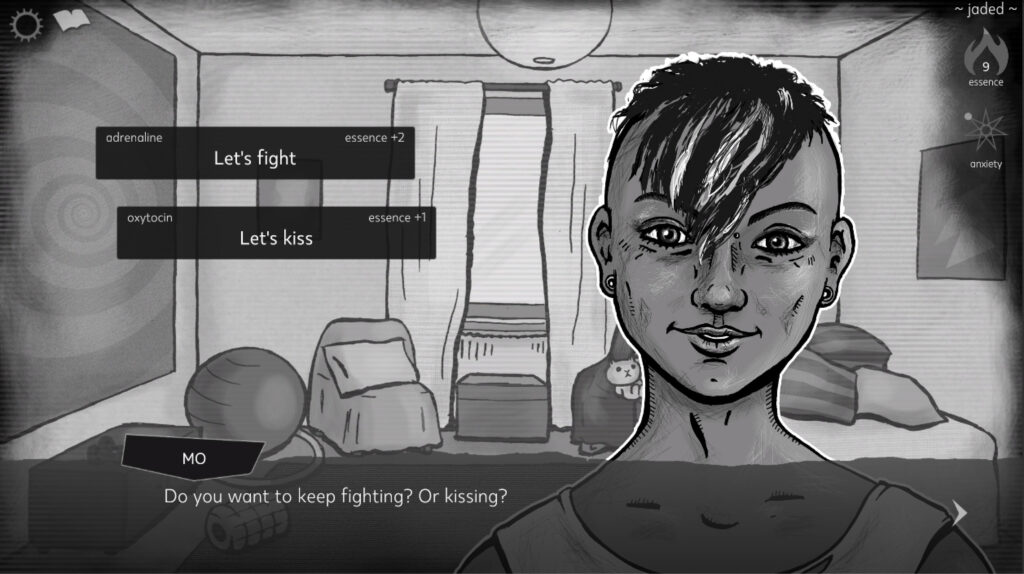

As I previously stated, characters have functions within the game’s system. On each weekend in Knife Sisters, Leo can date one out of three characters: Naomi, Mo, and Vicki. They’ll have playdates, which I’ve tried to design to give the player lots of freedom when it comes to how these scenes will play out.

And then, each Sunday, Dagger invites Leo to her room for a ritual, during which she will introduce Leo to a new assignment, as well as evaluate the last one.

Meeting with Dagger is not something you can back out from. The storyline with her has to be considered the main story, and the dates with the characters are side-stories, even though they will affect the outcome of the main story.

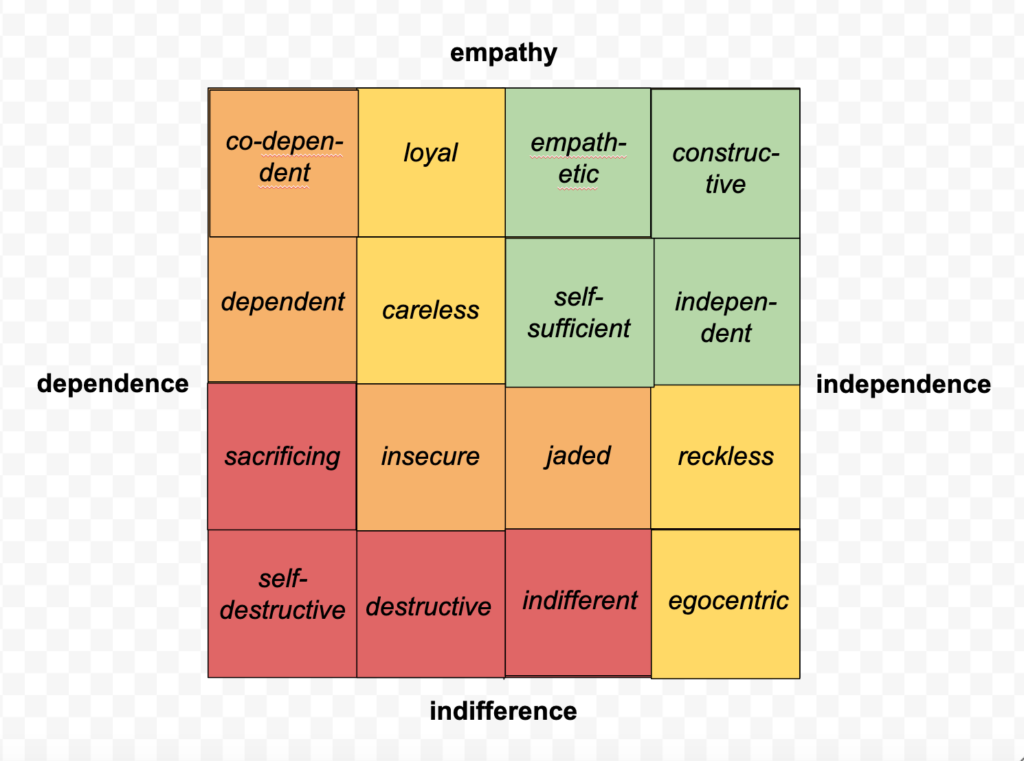

Having the relationship with Dagger being the main story was a choice I made because I wanted this story to be about dependence, and the idea was to have Dagger wanting you to go into a rather dysfunctional relationship with her – and then have the other characters function as counterweights to that. Depending on how you play, you’ll move on a scale related to dependence and empathy, which will also constantly shift Leo’s mood. The dependence value is mostly connected to Dagger, whereas the empathy value is connected to how you interact with other characters – your lover/s and friends.

What I wanted in Knife Sisters was that Leo’s relationships would serve as a counterweight to the rather dysfunctional relationship they would have with Dagger. The characters would also represent different sexual practices that the player might want to explore, such as being a top, switch or bottom. Apart from that, the characters had some different traits, for instance one is a cis woman, one is an androgyne non-binary, and one is a femme trans woman. I didn’t give the player any opportunity to date cis men, which means that the game caters mainly to players that are interested in women and trans people. (There haven’t been many players objecting to this – maybe because the game is pretty clear about what to expect.)

Maybe it sounds cold to say that characters represent functions? I don’t think it is. That games are systems is just a fact, and characters in games will always be utilities in that system, but of course, that’s not everything they are! The main goal of relation games is to evoke emotions, and if characters were only utilities, that goal would be impossible to reach. So the game’s characters are both functional and portrayed as close to real humans as we can possibly make them.

Knife Sisters is just one example of how relation games can be made. There are definitely flaws in the game’s design, and design choices we made sometimes had a bigger impact on the story than I would have wanted them to, but that’s what it’s like to make games. You can’t fully know what you’re making until it’s done and players start playing. That’s also the fun part! Let me know if you have experiences from playing or creating relation games. What did you learn from that?

Comments are closed.

Pingback: Would you like being forced into a relationship? – Transcenders Media