Is the goal to make players feel good?

In this series of posts about relation games I’ve been discussing game and narrative design from a relational perspective. I’ve been meaning to explore the role of player agency in games centered around relationships.

I also posed some specific questions:

Should players get a wide variety of romanceable characters to choose from, and be able to shift the relationships according to their preferences, or could it be meaningful to exhort players into having relationships they wouldn’t choose for themselves to convey a specific story?

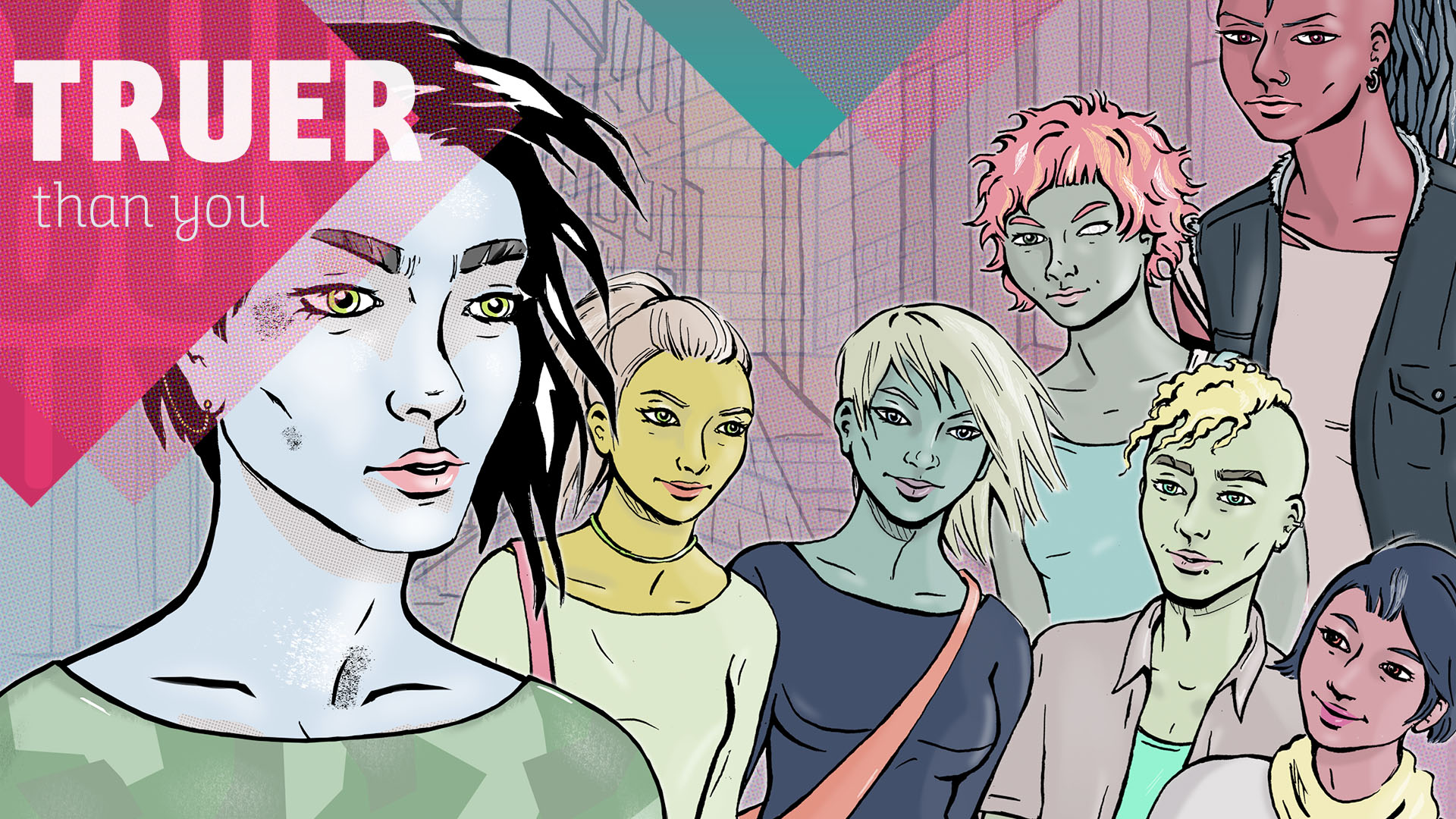

I believe both these questions could be responded to with a yes… depending on what type of game you want to make. Catering to players’ wants and needs is one way of addressing relationships in games, and it’s probably the most common route to take – but it’s not the only one. In the end it comes down to what the purpose of the game is – is it to make players feel good and offer them the fictional relationships they want to have? Then covering a range of options that is as suited to the target group as possible would be the best thing. Players try to satisfy their needs while playing – and being able to shift the relationships according to their preferences will make this easier. But making players feel good isn’t always the goal. Sometimes you want to explore a certain issue that might make some players uncomfortable. For us, that’s fine – but that comes with an extended need for communication. Being clear about what to expect is important, as well as accepting that players might – or will – react.

Working with content warnings and information is one way to prepare players for experiences that they might not fully enjoy. Especially when you are working within a genre where many games are based on fulfilling the wishes and needs of players by letting them romance characters. Then, if you include routes where the relationships aren’t completely healthy or don’t go well, you might break the expectations of the genre, and players might need to have some preparation for that. As a creator of that kind of game, you would also need to be prepared that some design or narrative choices might have a – sometimes – unexpected impact on players. I’d say it’s impossible to completely analyze a game during the development process. Doing a lot of user testing might bring issues to the table before release, but it’s definitely not failproof.

Bringing what we've learned into Truer than You

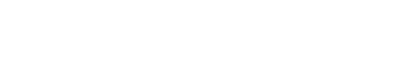

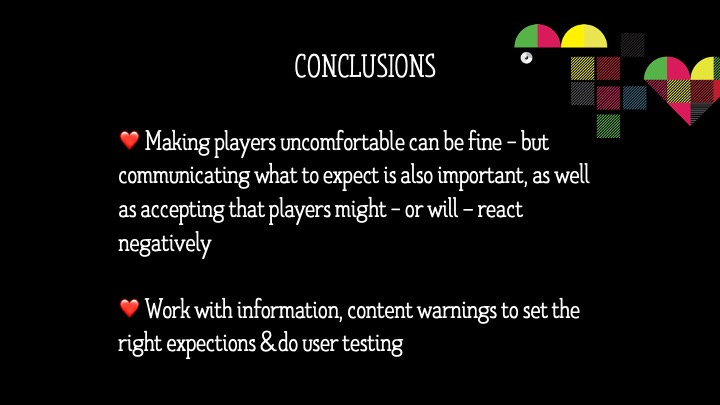

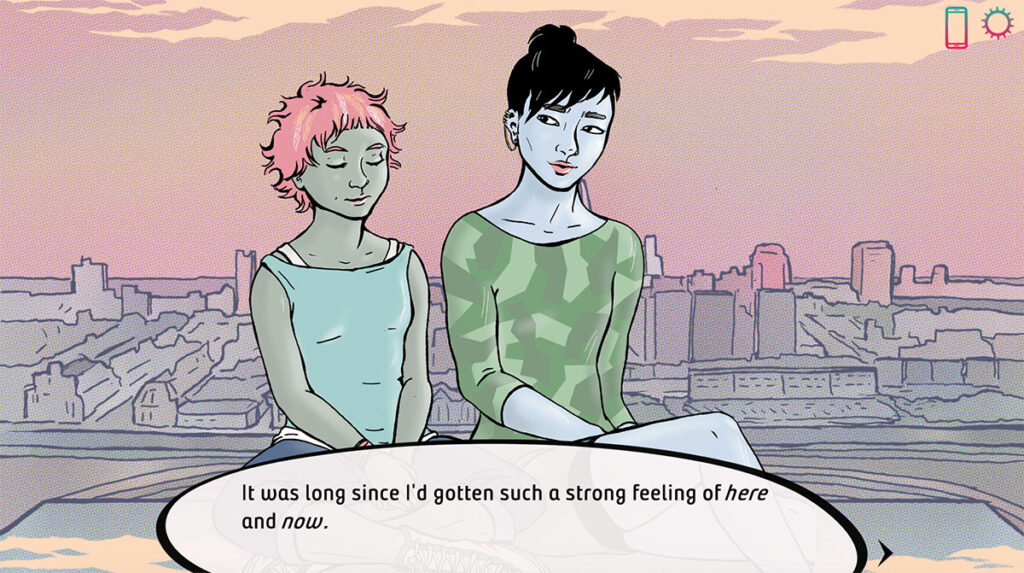

When developing our new game Truer than You, we’re aiming to implement some of the things we’ve learned from making Knife Sisters. In this game, you play an androgyne character called Rin, who’s recently moved to an unfamiliar city to start a new life and a new position at the secretive company Truer than You, specializing in renting out actors for real life situations. There are rules you have to follow – for instance, you can’t have relationships with people you meet through your work – but that’s something that could happen anyway… and that’s how you get to know Ariel, Indira and Sylvester, the characters you can form closer relationships with.

This time we’ve chosen to have branching storylines following those characters, instead of having them complement a main storyline connected to another character (Dagger), as we did in Knife Sisters. That’s not only because some players objected to being forced into the relationship with her, but also because this game has a whole other set of themes than Knife Sisters, that we see could be better explored by connecting them to the characters. We think that this design will increase the desire to replay the game, and make the player feel more in charge of the story. Hopefully, people will also perceive it as less linear. In Knife Sisters, you do have a lot of agency when it comes to how each scene plays out, but not as much when it comes to affecting the main storyline’s course of events. This is perceived very differently by different players, but we’re eager to see what players think and feel when the story changes a little more.

What do strong emotional reactions to your game mean?

In the end, it’s impossible to cater to all your players’ wishes. So you’ll need to accept that people will get disappointed at times – but, like the player who wrote an angry message, they might come to enjoy the game anyway! Strong emotions connected to your game show that people have engaged with it. Emotions aren’t always easily interpreted, and the systems for leaving feedback don’t necessarily cater to that complexity. You might engage heavily with a game, but still decide to give it a “not recommended” review on Steam – because it left you with negative or complex emotions. But negative emotions also teach us things.

For me, I don’t think making players feel good is a goal, but rather to make players feel, period. To evoke many types of emotions, ranging from good, to sad or even angry. If we make a game that has the player coming back to it in their mind, over and over, then we have succeeded.

What do you think? Please let us know in our social channels.