Relationships and gameplay

If fictional relationships feel real, as I proposed in a previous post, then we need to be mindful of how we utilize characters and relationships in games. Why are the potential relationships there, and what do we want players to feel? Most often, we are not entirely free when we design a game – there are constraints. Being indie developers with limited budgets, there might only be so many characters that we could offer our players to form closer connections with. So how do we choose those characters and relationships? Here I’ll present some different approaches to consider when designing a relation game.

Characters representing functions or symbols

I think it’s pretty common to have characters display very different traits, which by extension might mean that the characters have different functions (gameplay- or story-wise) in the game. They might also be connected to some kind of already established symbol, system or archetype. Connecting characters, game components or content to existing symbols/systems is a very common way to go about designing in the first place, since it helps us conceptualize things and put them into context. It could for instance be using the Tarot deck to base game content upon, like Simogo did in Sayonara Wildhearts. Using something that is already established might also help players to more easily understand the game. This way of thinking can be applied also to deciding upon characters/relationships and their roles in the game, and I’ll take some examples below.

Three types of practices

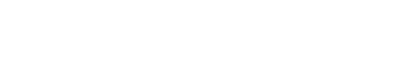

In Knife Sisters, I wanted the dateable characters to represent different types of BDSM practices: namely being a top/domme, bottom/sub or switch. It’s sometimes hard to backtrack how design decisions are made, but this idea came very early on, and preceded the choice of characters – which means that the characters are designed to give the player the opportunity to explore different sexual practices.

I wrote more about the design of Knife Sisters in this post, and about BDSM in games here.

Three types of love

Another game that might be applying this is Hades, the relationship heavy roguelite where you battle your way out of hell – also one of my all time favorite games. In this CBR article, Noelle Corbett states that the three characters that Zagreus can romance could be seen as representing different philosophical conceptions of love: philia, eros and agape.

- Philia is the one sometimes called platonic love, or siblingly love, represented by the relationship with Dusa.

- Eros is the type of love driven by desire and sexual passion, in the game represented by the relationship with Meagara.

- Agape is a kind of transcendent, persistent and unconditional love, in the game represented by the relationship with Thanatos.

The game uses characters with different functions to have the players explore different types of love and kinds of relationships. This diversity might motivate the player to keep playing, to experience all of its variations. It’s also perfectly connected to the theme of the game – that our relationships form who we are, and affect our fate.

(Connected to this: when I played Hades and Zagreus tried to romance Dusa, she told him that she did have feelings for him, but she wasn’t attracted to him sexually – something that Zagreus responded to in his usual happy-go-lucky way, taking it very well and saying that he respected her feelings. Me, who is very emotion focused, missed seeing a more emotionally affected response from Zagreus. For me, the game would have grown even more if Zagreus, all while respecting Dusa, could have displayed some disappointment or sadness that Dusa didn’t reciprocate his feelings – but maybe that’s just me.)

Connecting relationships to other game mechanics

I’ve been discussing connecting characters and relationships to the game design in a very high-level, conceptual way. Characters and relationships in games could also be tied to other game mechanics, meaning that the relationships will affect the outcome of other gameplay features (such as battles). This is also done in Hades, in the way that nurturing the relationships will unlock better companions, which could then be used in the battles. This has both ups and downs – the downside would be that you’re not given the chance to explore those relationships freely, instead you might feel obliged to do so, to gain more powerful companions. On the other hand, by encouraging the player to form relationships with all three characters (and then giving the player the option to make the final decision on how far to take it), they make sure we get to have one of the first openly pansexual and polyamorous main characters in a (more) mainstream game, which is amazing.

That’s also one of the answers to a question I posed in a previous post of this series: Could it be meaningful to exhort players into having relationships they wouldn’t choose for themselves to convey a specific story? I think it’s definitely meaningful in Hades, even though I also objected a little to having it tied to other gameplay mechanics. It has to be done with an understanding that this will affect the player’s decisions and experience of the story.

Gender variety

Another pretty common way to make up a cast of characters – at least in queer games – is to work with gender variety. An example is Boyfriend Dungeon by Kitfox Games, where you can date your weapons in human form, consisting of men, women and non-binary characters (and they also have a character called Dagger… or, who is a dagger, rather). Gender variety could also be said to be used in Hades, where you can date a woman, a man and a Gorgon head (!). Of course, their gender is not the only important aspect of the characters – dateable characters also have differing personalities and traits – and when all the dateable characters are of the same gender, the variety of personalities might become the main factor that separates them – like in Amnesia.

Relationship variety

A complimentary way to think about characters and relationships could be to base it on the notion that it’s the relationships rather than the characters that should offer variation. When in an in-game relationship, things might work out differently depending on the player’s choices, and the designers’ values and norms play quite a large role here. If we have routes with endings that are supposed to be bad, good and in-between – how do we decide what’s a good ending and not? The Very Common Way™ of doing it is to have the romance be the good ending – they lived happily ever after – and the breakup as the bad ending (well, and sometimes death, too) – but should it always be that way? It definitely says something about how we value relationships, with a hierarchy where monogamous, evenly reciprocated, long-lasting love is the crown jewel, and other types of relationships aren’t as valuable. (An example of this is the somewhat derogatory term situationship that categorizes relationships that fall outside of this norm.)

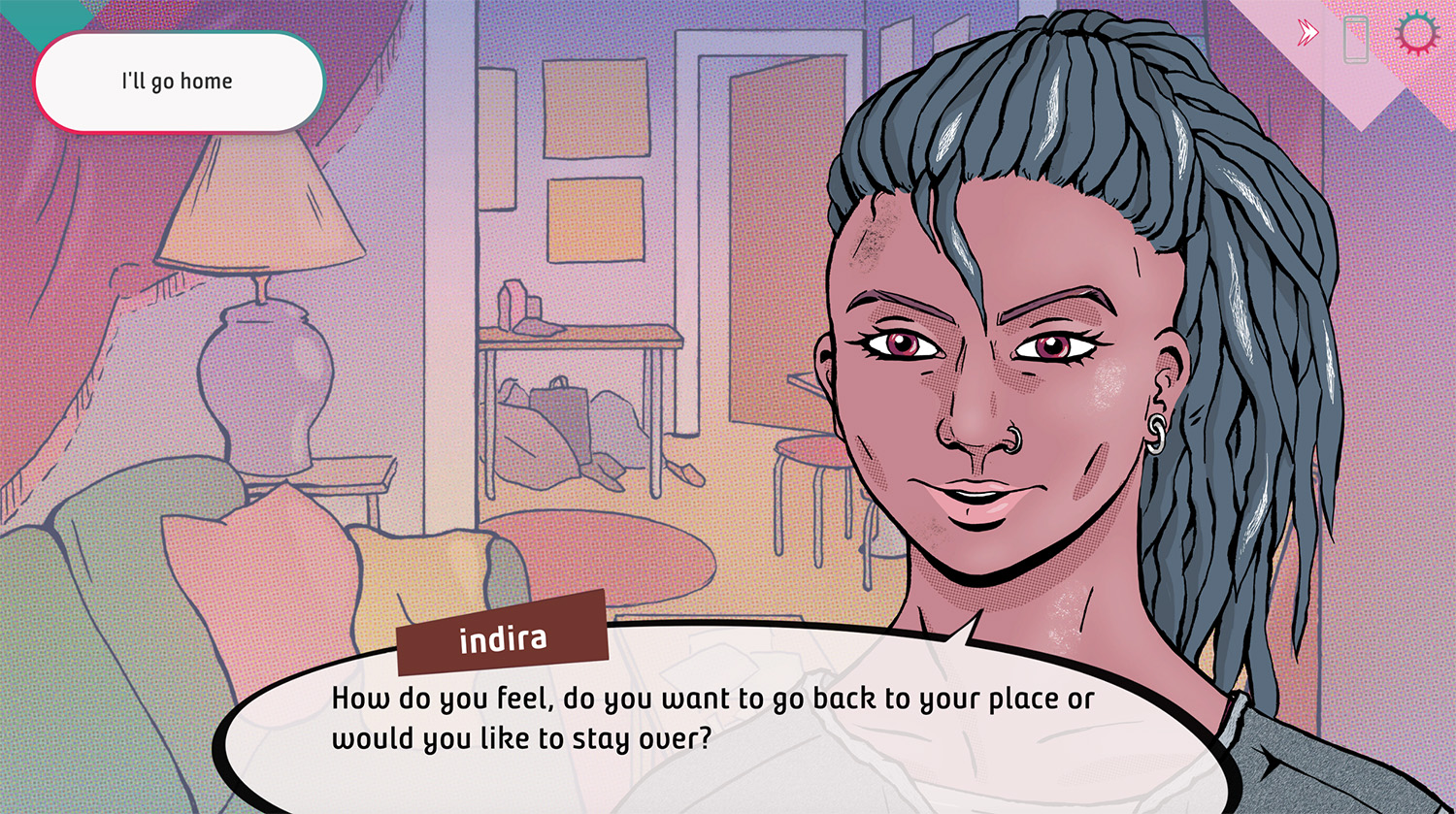

When we did a user test for our game in development, Truer than You, we got this feedback from a tester:

I have some triggers around Rin’s thoughts about Sylvester, when they think ‘well I guess I can think of him as a friend if he already has a girlfriend’ – but I don’t know how you plan to work with that, if that relationship will circle further around the infidelity thing, or, for example, end up in some kind of relational non-binary (where love and friendship would be the binaries). I would prefer the latter, but I’m biased because I’m a bit starved for such stories.

This response reminded me that all players do not want romance or friendship, but might actually want to explore the in-betweens.

It’s very easy to use our own values and views as a baseline, forgetting that other people might not function or feel the same way as we do. For example, if you’re a romantic, it’s very easy to make the ‘true love’ ending into the best ending – but does it have to be that way?

What are your thoughts around character and relationship design and variety in games? Let us know in our social channels!